Tribute

"Welcome to our tribute page, a dedicated space honoring the extraordinary individuals who served on Yosemite Search and Rescue and are no longer with us. This page is a testament to their unwavering dedication, courage, and the profound impact they made within the Yosemite community and beyond. Brief biographies and obituaries you find here shares the stories of their lives, their heroic efforts, and their contributions to saving others while embracing the spirit of adventure and service that defines YOSAR. We remember and celebrate their legacy, ensuring their memory lives on in the heart of Yosemite and in the stories of those who knew and admired them."

-

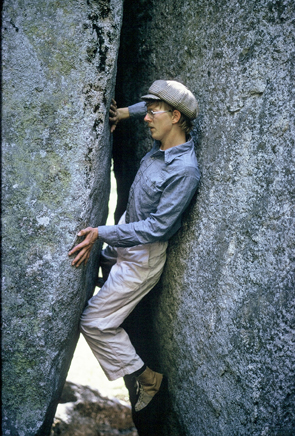

Pioneer of Yosemite SAR, Paramedic, Mountaineer, Mentor

Mead Hargis was a foundational figure in the early days of Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR), helping shape the team, systems, and ethos that define it to this day. Arriving in Yosemite in the early 1970s with his wife Tina (now Christina), Mead brought with him exceptional climbing skills, a deep sense of responsibility, and a quiet confidence that made him a natural leader in some of the park’s most demanding rescue operations.

Mead served in many roles—Camp 4 ranger, Little Yosemite Valley ranger, Tuolumne Meadows winter ranger, and eventually TM SAR Coordinator. He was instrumental in creating the first Tuolumne rescue cache, now the site of the current field office. He also helped initiate broader recruitment for SAR teams by sending notices to colleges and climbing shops—well before digital outreach existed—expanding the team’s skill base and diversity.

In 1977, Mead attended a paramedic program affiliated with Stanford and is believed to be among the first—if not the very first—EMT-Paramedic in the National Park Service. His medical expertise elevated the standard of care in the backcountry and inspired others to follow his lead.

He played key roles in some of Yosemite’s most significant rescues, including the Gaylor Lakes plane crash and the 1980 Yosemite Falls Trail rockslide, both documented in Butch Farabee’s Death in Yosemite. He mentored countless young rangers, modeled safety and calm under pressure, and brought a thoughtful, systems-based approach to backcountry emergency response.

Known for his integrity, dry humor, and relentless focus on safety, Mead left a lasting mark not only on YOSAR infrastructure and protocols but on the people who worked beside him. Friends remember him belaying partners while pretending to read a book, or leading teams through whiteouts with just a compass and instinct.

Mead later worked for the U.S. Forest Service in Utah, where he continued to innovate until early-onset dementia forced him to retire. He passed away far too young, but his legacy lives on in the people he trained, the rescues he led, and the culture of professionalism and care he helped establish in YOSAR.

He should be remembered as one of Yosemite’s true SAR pioneers—a steady hand in chaotic times, and one of the quiet architects of the team we know today.

-

SAR Member

Photo by: Dean Fidelman

Micah Dash 32, was born to Anita and Eric Dash of Lancaster, California. His passion for the outdoors began with his involvement as a competitive ski racer and he cut his teeth in the mountains backpacking with his father in the Sierras of California. After high school Micah moved to Leadville, Colorado where he started technical climbing and courses in guiding skills at Colorado Mountain College’s Outdoor Leadership Program. This led to a job instructing for Pacific Crest Outward Bound of the Sierras and then to a position with the prestigious Yosemite Search and Rescue team, during which time he developed world class climbing skills. He took these skills abroad to the great mountain ranges of the world, where he completed major expeditions, all while finishing a B.A. in History at University of Colorado at Boulder, CO. As a professional athlete for Mountain Hardwear, his cutting edge ascents around the world include: Pakistan’s Cat’s Ear Spire with Eric Decaria; the first ascent of the Shaffat Fortress in Kashmir, India with Jonny Copp; a free ascent of El Cap with Matt Segal, and the first free ascent of Nalumasortoq in Greenland with Thad Friday. Micah’s uncompromising passion for his family and friends is matched only by his love for climbing. His indomitable spirit for adventure and amazing perseverance have molded his careers as a professional climber and inspirational speaker. Micah is born showman — equally comfortable holding court in front of thousands at mountain festivals as he is with a few friends around a campfire. His renowned self-deprecating sense of humor and constant comic relief are well known, even in the face of life threatening situations. He has referred to himself as the Woody Allen of alpine climbing, and once said of an uncomfortable bivouac on a wall, “I’ve worn yarmakas bigger than this bivy ledge.” Micah would gladly give the shirt off his back to his friends and family, as well as eat all the carrots in their fridge without asking. He is deeply loved and his powerful personality is an inspiration to so many around the world.

-

SAR Member

Zach Orman, 28 Died in a paragliding accident on April 7, 2013 in Tucson, Ariz. Zach was born in Merced, Calif., and grew up in Murphys, Calif. He graduated from the University of California Santa Cruz with a degree in Neurobiology. He then spent three years working for Yosemite Search and Rescue and as ski patrol around Lake Tahoe. He was in his third year attending University of Arizona Medical School, where he led the Wilderness Medicine Student Interest Group. He was elected to the Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) Honor Society and received the AOA Gold Award for Humanism. Those who knew Zach remember him as an exceptionally smart, humble and empathetic person. He is survived by his parents, Rodger and Holly Orman; sister, Emily; girlfriend, Becca Dennis; grandparents, Bernie and Betty Orman and Marvin and Dinah Taub and aunt, uncles and cousins. A Memorial Service was held on Wednesday, April 10, 2013 at Temple Emanu-El in Tucson, Ariz. Contributions can be made to the University of Arizona College of Medicine in his name.

-

SAR Member

Photo by: David Murphy

On October 15, 2024, Yosemite Search and Rescue Team member Chris Gay died in an accident on Mariuolumne Dome. This is a profound loss for the YOSAR family and for all of us here in Yosemite National Park.

Chris was a true Yosemite Search and Rescue hero and valued member of our SAR team. He would drop everything to help his friends, teammates, or visitors in need. Over the past nine years he responded to 179 SAR incidents, and many other incidents including his most recent deployment for hurricane response, where he made significant, lasting, positive impacts across the nation.

Chris spent years exploring our mountains and other ranges around the world with a quiet and friendly presence wherever he went. As a climbing steward, he shared his desire to climb routes with Lord of The Rings references and taught and shared his love of climbing and the park to others. During quieter times, those who got to experience his musical talents were always in for a real treat.

We wish Chris safe passage on his journey to Valinor – J.R.R.Tolkien’s "Land Across the Sea"--a place for the immortals.

-

Yosemite National Park, CA - Jack Dorn, 30, formerly of Utica, was killed Monday when he fell 400 feet as he sought to help rescue two stranded climbers, rangers said.

-

SAR Member

Photo by: Dean Fidelman

Last Flight of the Ravens— By James Lucas

“They’re missing.”

Charley Kurlinkus, a BASE jumper and friend of Dean Potter and Graham Hunt, called me with those loaded words at 11 p.m. on Saturday, May 16. At 7:25 p.m., Dean and Graham had jumped from Taft Point, a promontory 3,000 feet above the Yosemite Valley floor. They’d been missing for over four hours. I tried to return to sleep, but couldn’t. Charley had also called me the year before.

I’d been in Zion National Park when Sean “Stanley” Leary was reported missing. I began searching for Stanley the day after Charley called. Less than a day later, Potter flew in from British Columbia, where he’d been wingsuit jumping. He met us at the base of the Third Mary peak, near the ridge where Stanley had crashed. Dean wanted to climb to Stanley’s body, put the body in a haul bag, and carry it down His emotional arrival had caused a groundswell among the other climbers gathered, rallying everyone to action. Dean and Stanley had a “brothers’ bond,” an agreement that in the event of an accident each would find his friend’s body before the authorities. Potter raged up the germanely named Gentleman’s Agreement, an 800-foot 5.13 on the steep south face of the Third Mary. He held Stanley’s body, still wrapped in his wingsuit, while an NPS helicopter flew overhead, performing a reconnaissance flight for the body removal. The next day, with the help of the Zion SAR, we recovered Stanley.

Dean was like that, charging in with emotion then simmering. After Zion, we fought. I’d written an obituary for Stanley for the California climbing gyms that was picked up by Alpinist. Dean contacted me.

“I haven't read your obituary but some friends have and they all recommended that I don't look at it,” he wrote, saying it felt "light" and "weak,” and adding: “I left out the really insulting words.”

Dean contacted the editors at Alpinist and the article was removed. “I think it's important for journalists to understand how meaningful articles, and especially obituaries, are to the community,” Dean told them.

I called Dean, talked about the times Sean and I had climbed together, worked together and hung out. I explained my motivations for writing about Sean and we resolved the issue.

“I am just one guy and speak from the heart,” he said, apologizing. “Thanks for understanding, James. I'm impressed with your composure and insights.”

A month after Zion, I acquired a framed picture of Stanley BASE jumping in Patagonia on El Mocho, and gave the photo to Dean. He was again appreciative, apologetic, nice and fun—Dean at his best. The brooding nature and intensity I had experienced, though, were what earned him the Valley nickname the Dark Wizard. After Stanley’s death, Dean took some time off BASE jumping, but soon returned to his “dark arts.”

“Grahambo” was a lighter spirit. When Stanley crashed, Graham had left a jump site in Los Angeles, and also met us at the base of the Third Mary. A few months later, he and I reminisced about Stanley while engaged in one of the many odd jobs that kept us afloat in the Valley, scrubbing the ketchup slime out of the Yosemite Village garbage cans.

“Stanley was a mentor,” Graham said during our 2 a.m. shift. Graham, Dean and Stanley had often jumped together. Yet Stanley was dead. We scrubbed harder. After Zion, Graham moved into Stanley’s El Portal trailer, caretaking the property.

Another night when we were supposed to be cleaning, Graham never showed up to work. I was pissed. I figured he’d died BASE jumping. The Curry Village bathroom tile wasn’t going to scrub itself. I cursed him. He showed up the following day, having spent the night at the “John Muir Inn,” the Yosemite jail. Rangers had arrested him while he was packing his chute at Mirror Lake, the landing zone for the Half Dome jump. Graham lamented the temporary loss of his wingsuit and rig. He complained about the rangers. I reminded him that he was the most prolific jumper in Yosemite, and suggested that a night in the jail and dropped charges were a small price to pay for a hundred Yosemite jumps. In my mind I recalled how Tom Robbins wrote in Still Life with Woodpecker, “Unwilling to wait for mankind to improve, the outlaw lives as if that day were here.” I was happy that a Yosemite brother was there to scrub tile again with me.

“I decided to get a blue heeler and name her Whisper,” Dean said from beneath a tree at the base of the Nose a few years ago.

“But you hadn’t even met her,” I said, laughing at Dean’s impulsive nature. Dean had had an idea, though, and made it happen. Whisper barked a lot, but Dean insisted on the name. He brought her everywhere with him: the base of El Cap, the Yosemite Lodge cafeteria, the headwall of the Salathé. He even BASE jumped with her.

In the last few years, Whisper had become an extension of Dean. She joined Dean and Graham in Yosemite West, where they were clearing trees on Dean’s recently purchased property. He’d been in the Valley sporadically over previous years, but here much more in recent ones, working on a house with his life partner, Jen Rapp. To me, having Potter around the Valley felt reassuring.

I had two quintessentially Dean Potter experiences in the last year. One evening in Camp 4, Dean offered to climb Freerider a free route up El Capitan, with me, leading the easier pitches so I could be fresh for the difficult climbing.

While I worked on the route, a raven opened my backpack and ate my food while I was climbing, then met me on the summit. I thought of Dean immediately since the Dark Wizard loved these intelligent and mischievous birds. Even though we ultimately didn’t climb together, I was flattered that one of my climbing heroes would offer to help me. He was there in spirit.

When Charley called this year, I knew. Dean and Graham had attempted a difficult BASE jump; it was one they’d done before, but it still required precision to fly through a small notch. Graham jumped first that evening. Dean jumped after him, flying low. Graham turned left and then back right. He missed the notch. He flared and impacted the wall with his chest. Dean cleared the notch but lost altitude and crashed headfirst. They both died on impact. Wind and the close proximity of the men may have caused the crash. Jen, who was at the exit point taking pictures, had watched from above and heard impacts, but hoped that the men had somehow survived.

Two nights after the accident, the Monkeys, the loose crew of modern-day Yosemite rock climbers, met at Stanley’s trailer in El Portal to remember Graham and Dean. Yosemite locals, BASE jumpers and climbers from around the world gathered. We cooked, ate and drank for the hangover. Some had been to Taft Point that day. Others had gone climbing. Some had cried by the river. We all dealt with the darkness that had swept over Yosemite in the only ways we knew how.

I drove into the Valley floor the next day. My head throbbed. The clouds lifted above El Cap and the ravens returned to the sky.

James Lucas is a Senior Contributing Editor for Rock and Ice

-

SAR Member

Patrick M. Dougherty, born in Chico, California, and raised in Yreka, passed away in Reno, Nevada, at the age of 38. A dedicated rescuer, skilled paramedic, and passionate outdoorsman, Patrick devoted his life to service, adventure, and the pursuit of excellence in emergency medicine.

Patrick’s path led him to Yosemite National Park, where he served with Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) as one of the youngest paramedics ever hired. His courage, technical skill, and calm leadership in the face of danger made him a respected and trusted member of the team. Yosemite became a defining chapter in his life, blending his love of climbing and wilderness with his deep commitment to helping others.

Patrick’s career in emergency medical services spanned multiple agencies, including Enloe Medical Center, First Responder, Side Trax, West Side Ambulance, and Rigging for Rescue, where he refined his technical rescue expertise. His drive for growth and mastery extended to his work with the Tactical Emergency Medical Service (TEMS), serving alongside regional SWAT and federal teams. Known affectionately as “Doc,” Patrick was a steadfast presence on missions that required precision, courage, and trust.

In 2016, Patrick achieved his dream of becoming a flight paramedic with Care Flight in Reno, Nevada—a role that perfectly combined his skill, compassion, and love of adventure. He thrived under pressure, saving countless lives and forming lifelong bonds with his colleagues.

Patrick will be remembered for his generosity, humor, and deep love for the natural world, animals, and family. His legacy lives on in the mountains he climbed, the lives he saved, and the many people he inspired through his service and spirit.

He is survived by his parents, Patricia and Michael and his brother, Andrew.